I don’t want this site to be all about our particular story, but I think it’s important that I tell it, just so people understand what motivated me to create this site.

In 2019 my wife and I moved our family back to Australia, having spent the last 8 years living in the United States.

When we left our three children were little, but when we returned they were nearly adults, and our home in inner-city Leichhardt just didn’t have four adult sized bedrooms.

I had always wanted to live in the bush, so before we left the US we had been looking at properties in Burra (just outside of Canberra).

We fell in love with the first property we saw, it was around 150 acres, had existing farm infrastructure, a nice modern house, and it was in our price range.

Having found our dream home in the first property we visited, we had some spare time so I talked Jennifer into visiting Braidwood to see what they had there.

The first home we saw was on the northern side of Braidwood, and it needed a lot of work. It was a beautiful old home, but it just wasn’t for us.

The second home we were planning to look at was on the western side of Braidwood, and we asked the real-estate agent about as we left the property she had just show us.

She mentioned that she had priced the property, but the owner decided not to use her to sell the home, so it would be inappropriate for her to comment.

So we drove to the 2nd property, in Bombay, and it was along a 7km dirt road. It was a ways out of Braidwood, but the minute we drove up the driveway the house in Burra was no longer my dream home.

The owner showed us the home and I asked her about the 360 acres of bushland that came with the house. Rather than describe it, she then lead us on a 2km bushwalk through the property.

I was sold. I asked her if she would take an offer of the asking price, and she agreed. I then had to convince Jennifer that we could make this work; the property was beautiful, but it was a good 25 minutes into Braidwood, and Braidwood is a good 90 minutes from Canberra.

A few weeks later we visited the property with the kids and Aspen (our Doberman), and we agreed to buy the property.

Because Bo and Andrew (the owners) were selling privately, they didn’t have a contract, so they approached an attorney who drew one up, and we put down a deposit.

The sale closed in late November of 2019, but because Jennifer and I were overseas, we gave Bo and Andrew a temporary lease, so they could stay a little longer and hand the house over to us when we returned in mid-December.

On the 17th of November I woke up in a hotel room in London to a Facebook message from a friend in Australia telling me that there were fires in Bombay, this was the first I had heard about any fires in Australia.

Jennifer was already back in Sydney, but there was little we could do. I managed to get a message through to Bo, and she explained that they had stayed on the property as long as they could preparing, but that they didn’t know if the house had made it through the fire. A neighbour later told me that they had stayed back to fight the fire and had to be told to get out. Lucky they did because the fire came so close to the home that the PVC downpipes melted.

Even though they no longer owned the house, Bo and Andrew not only worked feverishly to ensure the house had the best chance of survival, but they cut their way back into the property after the fire and did everything they could to clean the house, including power washing the external walls which were blackened by the smoke.

On the 10th of December we met Bo and Andrew at the house so that they could explain the operation and maintenance of the house, which is completely off-grid.

They were going to be a little late so they told us to get the fire-trail gate keys from a rock near the gate. This was the first time we were aware of any gate. On the previous inspections the gate was already open, and driving along a fire-trail was so novel at the time I had no idea where the property started and ended; all I knew was that the house was built in the middle of 360 acres so it didn’t encroach on any other property.

We didn’t want to live behind a locked gate, but we also didn’t want to upset our neighbours, so each time we came and went we would stop the car, unlock the gate, drive through and lock the gate behind us.

On one occasion the gate was already open so we drove through, only to return, discover the gate locked and that we had left the key at home. This meant we had to walk 2km along a dirt track, get the key, and walk another 2km back to open the gate.

Over the next month one of our neighbours would constantly remind us via text message to lock the gate, even though we always locked the gate, but we didn’t want to offend them, so we explained that we always locked gate, and kept locking the gate.

Then one day I met my neighbour Peter, and asked him about the fire-trail and the gate, and explained that the gate had been put their illegally. The road was a Crown Road, and it was illegal to have a locked gate on a Crown Road, further the gate wasn’t even installed on the property of the person who installed it, who actually lived in Canberra and rarely visited the State Forest they leased.

The next time I was reminded to lock the gate, when I still always locked it, I explained that I would no longer be locking it, and that was the start of my journey towards becoming an expert on road law.

As it turns out, the road had been a huge point of contention for many years before we arrived.

The road was a Crown Road that extended from Little Bombay Road to my southern boundary, and 90% of the Crown Road coincided with a fire-trail (the Butmaroo Fire-trail). In addition, the formed Crown Road didn’t follow the road reserve for 50m at the start, and deviated from the reserve by less than 10m somewhere in the middle for about 50m.

The Crown Road went through 1400 acres of gazetted State Forrest, which was managed by National Parks, and leased to a Perpetual Lessee, who had used it as collateral to take out a loan with the National Australia Bank.

As it turns out, the local council had issued development consent to Bo and Andrew without ensuring that the home had concurrent legal and practical access; the home had legal, and practical access, but not concurrently.

Having realised this mistake just after they issued the development consent, the council went looking for a scapegoat.

My neighbour Peter had built a small shed house (a shouse) on the eastern side of their property, which they used as a weekender. So the council accused them of living in the shouse illegally and demanded that they put in for development consent retrospectively.

When they applied for consent, they were told that the shouse could not be approved because the dwelling was 2km away from the fire-trail, and the fire-trail was their only fire egress.

This forced Peter to apply for development consent to build on the western side of his property (the same side as Bo and Andrew), and as part of his consent, the cost of upgrading the fire-trail to council specifications, so it could be transferred to council was foisted on Peter.

The cost of upgrading the road was over $200,000 at the time, and by rights the cost should have been part of Bo and Andrew’s development, which would have meant their home would not have been built at all.

Peter then spent the next 4 years fighting against the imposition of having to pay the $200,000 and realised that council could only impose this condition to a developer with concurrent access to the Crown Road; as Peter accessed his property via a 600m Easement over Bo and Andrew’s property, council had to remove the condition.

At a council meeting in 2016, the council discussed Peter’s application, Cr. Harrison rightly pointed out that it was not wise to knowingly allow a new application with a known access issue, while describing Bo and Andrew’s home as “illegal”, even though it was compliant with all development conditions.

He pointed out that Bo and Andrew would have trouble selling their home because it was illegal, but despite this categorisation the council issued an Occupancy Certificate to Bo and Andrew in 2019, when they put their home on the market.

It was clear that Cr. Harrison had absolutely no concern for Bo and Andrew, who had complied with every condition of council as they invested in the franchise of a Council approved home.

The simple solution to this problem was for someone to run a bulldozer 50m along the reserve (the paper road) so that stretch of road was no longer “trespassing” on the Lessee’s land, but as this was “Major works” Crown Lands refused to allow the residents to do it, and informed us that the work had to be done by a “Road Authority” such as council.

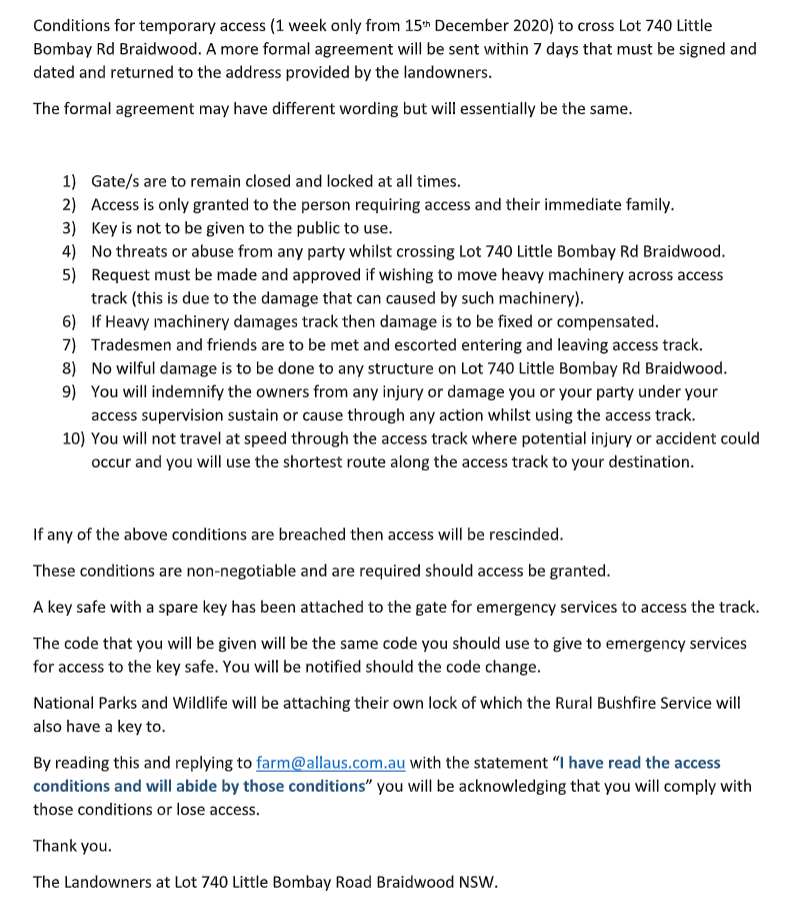

In 2020, the Lessee of the Crown Land where most of the road traversed, commissioned a survey and installed a new locked gate on the meandering stretch of the road, which this time was on their property, and demanded that all residents sign a contract that required the residents to obtain consent from the Lessee of any visitor to visit our home, including family.

Agreeing to terms like this may have solved our problem in the short term, but we already had legal access via a Crown Road. It was not as if we should have needed to enter into such an onerous agreement just to access our own home, and no sane person would buy a home where their only access is via such a tenuous agreement.

We contacted the council and asked them if we could pay them to run a bulldozer along the unformed section of road, but they refused, citing this as a “Your problem”, not an “Our Problem”.

So over the next 6 months, the residents had to drive via a neighbouring property, along a private road that added 30 minutes each way, while Crown Lands met with council to find a solution.

Not able to negotiate a solution with council, Crown Lands spent over $100,000 surveying the road so that it could be forcibly transferred to the council.

In 2022, the road was transferred by Ministerial decree, and the road issue went from being a “Your problem”, to an “Our problem for council.

In their desperation to stop it from being an “Our problem” council passed a new “Crown Roads Management Policy”. This policy acknowledged that the road was transferred to council (because council had no legal right to stop the transfer), but that as it was the policy of the council to refuse to acknowledge the transfer, and councillor who discussed the road issue with the residents from the perspective of it being a council road would be disciplined under councils Councillor Code of Conduct.

In practice, this meant that when residents contacted their local councillors in an attempt to try and resolve an issue that made their compliant homes illegal, councillors refused to discuss the issue, and deprived the residents of any way to discuss their valid concerns.

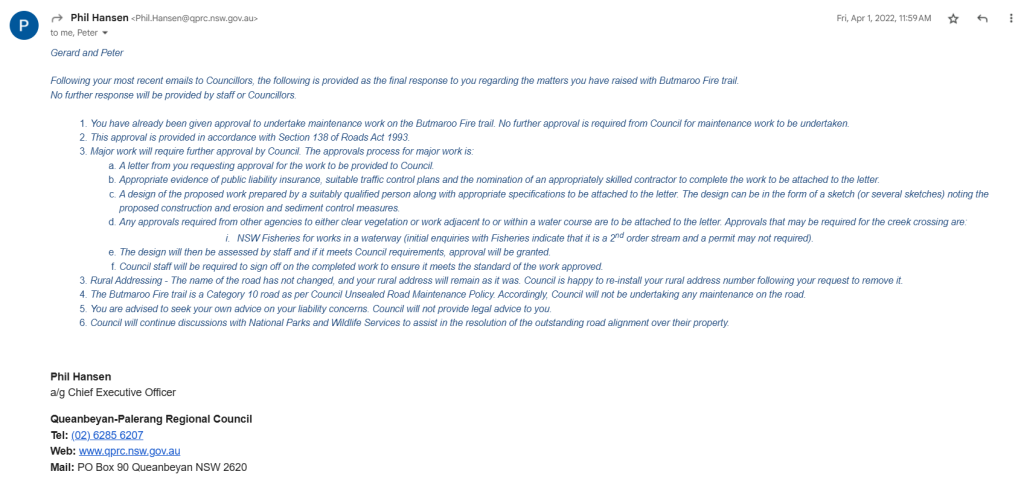

Council then claimed that the road was not maintained by them, that the road could be maintained by residents under a blanket consent from council, and that any work on the two creek crossings required consent from council under Section 138 of the Roads Act, along with a permit from NSW Fisheries (something that Council later agreed would probably never be granted by Fisheries to residents).

It took us another 2 years, but today the Crown Roads Policy has been completely rewritten to the point that it has no point, the state government have provided $500,000 to council to upgrade the road and the road has a name, but there is still an ongoing dispute over whether residents can legally maintain the road.

Council’s Governance Officer Caitlin Flint stated that Phil Hanson’s claim that no Councillors would speak to us about the matter was improper, yet new CEO Rebecca Ryan has refused to take any action against him, asking us to instead “trust her”.

In July of 2024 Cr. Mareeta Grundy took up our cause and her Question on Notice allowed us to force the discussion about who will maintain the road going forward.

During this meeting the senior staff positioned the residents as rogues, and implied that we build houses without consent and cut access roads through the bush. If this was actually true, it means that council has completely failed in its role as consent authority for development.

The CEO, Rebecca Ryan, finished the discussion by exposing council’s legal advice; that it is illegal for residents to maintain a public road, but as long as council continue not to prosecute this illegality, there is no mechanism to force council to do its compliance job.

Yes, that’s a long story, but trust me that’s the short version. In future articles I will explain the tactics we used to force this resolution, and outline what worked, and what didn’t.